Thank you to WFMZ for including me on a recent episode of Business Matters!

Thank you to WFMZ for including me on a recent episode of Business Matters!

Father’s Day brings up so many difficult feelings. While others are out celebrating their dads or honoring their memory, I have to build up the courage to make a phone call. Growing up, my dad and I had always been close. Despite my parents getting divorced when I was in third grade, I still saw him every weekend and I looked forward to our time together at his apartment a half hour away. We’d pop popcorn and watch movies on HBO. We’d go to his office and do “work.” He’d pay me to write out the envelopes for prospective clients. We’d go grocery shopping and out to eat. He’d take my friends and me to the mall and host sleepovers with my friends. We’d go to the laundromat every Sunday and race washing machines. We’d put the quarters in the slots and push them in to the machine when my dad said “Go.” We’d play games in the car like “Name That Tune.” He’d whistle a few notes of a popular song and I’d try to guess what it was. When I was in high school, we’d go to a local bar/restaurant for Karaoke nights. He’d even buy me my favorite drink—a fuzzy navel! I sang with the owner so he bent the rules a bit.

Anyway, my dad was my hero. He never missed a performance and there were a lot. He would even go to the same musical multiple times and sit in different areas for different perspectives. Every bank teller knew every accomplishment of mine and told me how proud my dad was of me every time I went to the bank with him. He was dynamic and creative and fun. He was also bipolar, though he was never diagnosed or medicated for the illness. This created lots of unnecessary stress and dysfunction in our already non-traditional family. He’d go from jokes and laughter to rage in a split second and the smallest thing could set him off. Actually, he handled the larger issues with far more calmness and grace. But a dish out of place or a dribble of milk on the counter and you could hear him for miles.

Our relationship became more complicated when I started living with him during my sophomore year of high school. He had an unstable girlfriend who moved in with us and faked a pregnancy and miscarriage (despite a full hysterectomy years before), and then cancer. She’d leave clumps of her hair around as proof, though she was really just pulling her hair out to suit her sordid narrative. For fun, she would take out her false teeth, pull her hair back from her forehead, stick out her tongue, and chase me around the house when my dad wasn’t around. She howled when they had sex and even told me that my dad prefers blowjobs with her teeth out. Ugh. Not information that a teenager needs to learn about her father. Anyway….

When we moved to a new house my senior year of high school, I co-signed under the impression that if something happened to him, I would still have a place to live. Now that I’m older, I know that unless a house is paid off, the bank will come to the co-signer for the mortgage payment. As a recent college graduate responsible for my own rent, I didn’t have the money for an additional mortgage payment so the house foreclosed. I also learned that my dad had taken several credit cards out in my name without my knowledge. To make financial matters worse, my dad’s name was on my checking and savings accounts so my accounts were frozen and I had no access to my money. Then my dad was arrested for insurance fraud and put behind bars for several years. Unable to pay off all the debt from my father, I had to declare bankruptcy at 22 without having charged a cent. Not an ideal start to life on my own. For the next seven years, I learned to live with little money and no credit.

Five years later, he got out of prison, but he wasn’t the same fun and supportive dad. He was hard and cynical. He made promises he never kept. I caught him in more lies than I can remember and he never owned up to ripping off all his clients. He also never apologized for all he’d put me through as a young adult.

Flash forward to the present. My dad, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s last year, is staying in an assisted-living facility an hour and a half away. I call him, but he rarely answers. I visit him from time to time and take him out for dinner and grocery shopping. He’s always appreciative and happy to see me, but the visits take a toll on my mental health. He seems to have forgotten all the hell he’s put me through and only remembers all the good things he’s done. Probably a defense mechanism so he can live easier with himself. I accept that and just want him to enjoy the years he has left. He’s lonely, though much of that is his fault. That’s punishment enough. I don’t need to make it worse for him. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t hard and I don’t struggle. Not just on Father’s Day, but every day.

I looked at the faces on my computer screen, the people in my support group with whom I’ve spent every Thursday night on Zoom for the past two years. As the facilitator, I try to stay positive, but one night I was really down. I had just gotten back from a girls’ weekend with two college friends, both of whom went on to have successful careers, one as a lawyer and the other as a high school principal.

I thought back to our college years and wondered what happened to me—the straight-A student who worked two part-time jobs, participated in choir, theatre, served as Philanthropy Chair in a sorority, and volunteered at a local school. I had looked forward to a bright future when all my hard work and dedication would pay off. And it did until a mental breakdown in my 40s upended my world.

Due to an unsupportive administration that exacerbated my mental health challenges, I had to give up my beloved career as a high school English and Drama teacher. As my college friends talked about juggling the demands of working full-time, raising children, and managing household tasks like cooking, cleaning, and paying bills, I felt like a failure. I can barely manage to work ten hours a week, my daughter is struggling with her own mental health issues, and my husband handles the majority of the household chores. I smiled and nodded, pretending to relate, but inside I felt broken and worthless.

As my support group shared how their week had gone, I debated whether or not to let them know how terrible I felt. As a leader, I didn’t want to take any focus off of them and I didn’t want to set a negative tone. But I needed to be honest. So I shared how difficult my weekend trip had been and how lonely and unaccomplished I felt.

Nicole, my fellow leader of the group, told me that she became a facilitator because I inspired her in one of the mental health courses I taught. She continued, “I know you feel like you’ve failed because you aren’t an English teacher anymore, but you are still teaching and impacting so many lives. More than you will ever know. So many people are here because of you.”

Another voice said, “I’m here because of you.”

Then another. “Me, too.”

My throat swelled and my heart filled with gratitude. A warm sensation spread throughout my body. I thanked them for their kind words and told them how much I needed to hear that.

Sometimes we can’t see what is right in front of us. Sometimes we get so caught up in what was supposed to be that we miss the beauty of what is. By pining for past employment or neglecting to explore other options, we rob ourselves of new and exciting opportunities and lasting, meaningful connections. We can still make a difference even if it’s not the way we had hoped or imagined. We can use our talents, skills, and experiences to enrich (even save) another’s life. I can’t think of anything more worthwhile than that. I may not have the money or the pension plan or the health insurance or the retirement benefits like I once did, but I have peace of mind and purpose and that is priceless.

When I’m feeling well, I feel very resilient, but when I’m not—when depression sets in as it inevitably does— I feel weak, like I’ve failed to stay well and I should have known better. I think, “How could I let this happen? Why didn’t I practice my coping skills better? How did I miss the warning signs?” I see others show remarkable resilience through unimaginable losses, severe illnesses, major defeats. I envy them as they bounce back or pivot or at least maintain a positive attitude. I think back to all the struggles and challenges I’d endured before my break—a chaotic childhood filled with divorces, arrests and restraining orders, bankruptcy at 22 due to cosigning with parent, father’s incarceration, three broken engagements, etc. I took it all in stride, barely missing a day of work. I prided myself on my resilience. Nothing seemed to bring me down until a toxic work environment and a cruel supervisor pushed me to the breaking point.

Now I can’t seem to bounce back, pivot, or think positively about anything. What happened to that resilient young woman who took everything in stride? My brain spins in an endless negative loop on a perfectly normal day. It can take the most positive event and turn it into gloom and doom. The slightest thing can set me back and undermine my confidence and worth. It’s like a dam in my brain has broken and it can no longer hold back the flood of negativity. Everyone around me seems to handle life with such grace, productivity, and positivity. I feel weak, lazy, vulnerable, embarrassed, ashamed, scared. I should be more productive, more grateful, more resilient—better.

And yet bipolar disorder is a brain disease. It clouds perceptions and disguises lies as truth. Maybe resilience looks differently for a bipolar person. Maybe resilience is getting up in the morning when a 100 lb weight is holding you down. Or showing up to an event when you want to isolate at home or finishing an assignment when your brain isn’t working. It makes no sense to compare my resilience to someone who doesn’t suffer from a brain disorder. A person with lung cancer will most likely not breathe as well as someone without it. It’s no weakness on that person’s part; it’s the nature of the illness. That person can try and try to breathe better, but it’s not going to happen. They can utilize tools that will help them to breathe easier, but they’re going to struggle to do it on their own. Isn’t the same true for bipolar? I can try and try to stay positive, to not let something get to me, but my brain will go there anyway. The brain can’t think and process things well if it’s sick so I have to use coping skills, medication, therapy to help me breathe easier, too.

It turns out my resilience shows the most when I’m not well. It takes strength to ride out the long and dark days of depression. It takes optimism to maintain a shred of hope when the brain tries to convince you it’s hopeless. It takes persistence to keep going when your body and brain want to give up. Resilience is shown in all kinds of ways and those with mental health conditions model resilience every day of their lives.

Sometimes you can do all the right things (e.g., practice gratitude, mindfulness, reframe distortions, use positive self-talk and affirmations, exercise, eat right) and depression can still rear its ugly old head in and leave you in a world of suck. I’ve really been struggling the past few weeks and my biggest fear is: what if I don’t get better? I know, rationally, that I will get better at some point and I just need to ride out yet another episode, but I still worry that no matter what I do I’ll never get better and I can’t live this way for the rest of my life. I need to remind myself that, as my therapist tells me, “that’s my anxiety and depression talking.” I need to challenge these distortions and tell my depression to “shut up!”

So let me reframe this distortion: “No matter what I do I’ll never get better.” This is not true nor is it helpful. I haven’t tried all possible medications and treatments so I can’t know that nothing will help (generalization). I also can’t know that I will never get better either (mind reading or predicting the future). However, if I tell myself that I won’t get better I will, no doubt, impede my progress.

A more rational thought would be: “There are many medications and treatments I haven’t tried. It may take time, but I will get better as I have many times before.”

Just by reframing my thought, I feel a little better. Each positive step I take is a step closer to wellness. Depression may have me in its grip right now, but I will get better. It’s only a matter of time.

I’m no scientist and I don’t remember much about Physics, but I know all about inertia. It is easy for me to get stuck in a rut and I have to really push myself to get motivated. Some days are easier than others, but one thing’s for sure: lying on my couch doesn’t help. Once I get sucked into the couch vortex, I can disappear for hours. One hour leads to another and another. Before I know it, the day is almost over and I accomplished nothing. Then I think of all the things I should have done. Then I feel the guilt and shame and worthlessness. It’s a vicious cycle–the less I do, the worse I feel, and the more negative my thoughts become. So what does this have to do with Newton’s first Law of Motion? Everything.

In a game of dominoes, the dominoes remain still until one topples. When one moves, it causes the next to fall and so on. Bodies are no different. That’s why I need to make sure I get up and move during the day. It doesn’t need to be exercise or anything in particular, but if I don’t force myself to get up, I can easily stay there for a long time. Then the feeling and thoughts get going and soon I’m spiraling down a dark dark hole. However, if I can take one step no matter how small–topple one domino–it will often lead to the next one and I gain momentum.

The tricky part is that unless I have to be somewhere, I tend to stay put. Then I feel even worse for not doing anything when I had the time and the means. I swear working full-time is what kept me sane all those years. The great irony is that my mental illness prevents me from working full-time: I can’t handle the workload or the level of stress I took on before. It’s a constant challenge, but I try to catch it early and set myself in motion, often through the encouragement or accountability by a friend, peer, family member, therapist, etc. Many have told me that having a pet has saved their lives. Their pets give them purpose and force them to get up and walk them, feed them, play with them, and care for them. My pet, a sweet rescue cat named “Cinnamon,” prefers the couch so he isn’t much help in the get-up and get-moving department. He does give me joy, though. Thankfully, I have other things that keep me moving.

Finding ways to build in accountability and maintain a consistent routine can help so much. For me, volunteering and partial programs gave me that structure when I wasn’t able to provide it on my own. I had a specific time and place I needed to be. My therapy appointments and peer support group meetings helped me to get out, even if just for an hour or two. I learned to be gentle with myself and give myself credit for even the small tasks I completed. It feels good to cross something off a list, no matter how small it is. Accomplishing a goal builds momentum and moves energy in the right direction.

I still find myself drawn to the siren song of the couch, but it’s getting easier to steer away toward brighter shores. Sure, there are days I succumb and and crash, but I give myself grace, get back in my ship, and move on.

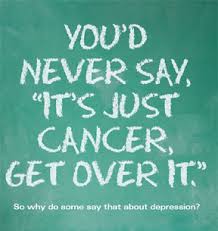

I don’t know how many times I’ve heard these responses to my depression. As if it’s that easy. Anyone who tells you “You’re just having a bad day. You’ll feel better in the morning” has clearly not experienced the crippling agony and utter devastation of depression.

Thankfully, there are programs in place that help family members understand and support their loved ones with mental illness. The Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA) and The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) run programs and support groups for family members and friends.

The Lehigh Valley DBSA holds weekly support group meetings on Wednesdays at First Presbyterian Church on Tilghman St in Allentown from 7-9 pm. Contact information can be found by clicking here.

Another resource to help friends and family members understand mental illness and support their loved ones is NAMI’s Family-to-Family program, a free 12-session educational program taught by trained family members who have been there.

If friends and family members are not able to attend support meetings or participate in programs, there are plenty of websites to guide them. I referred my husband here.

“Get over it.” This is one of the most frustrating responses I get during a bout of depression. Telling someone to “get over it” is like telling someone with broken legs to run a marathon. It defies common sense as depression affects the brain’s ability to think clearly in the first place. Others recommend going for a run or to the gym. If it were that simple, I would have already done that. I know that exercise helps with depression, but when just getting out of bed takes monumental effort, there isn’t much energy left for lacing up.

I don’t blame people who give this advice–in fact, I used to be one of them. I could never have realized the debilitating effects of depression until I experienced them firsthand. However, telling someone who is depressed to just “tough it out” or “snap out of it” points to a profound ignorance about mental health. No one would tell someone with cancer to just “deal with it” (nor should they), but depression is a life-threatening disease as well. Contrary to popular belief, depression is not just feeling tired or sad and upset over a recent loss. It is a serious life-long illness that requires treatment and while it can be managed with medication and lifestyle changes, there is no cure.

Sadly, there are many factors that prevent people from seeking help for a mental health condition. Perhaps the biggest deterrent is the stigma associated with mental illness. It seems mental illness only gets attention when some “crazy” person goes on a shooting rampage or a celebrity suffers a mental breakdown or commits suicide? This type of attention sensationalizes mental illness, instills fear, and attributes it to “the others”–often, the rich and famous or the truly criminal or deranged. It only perpetuates the stereotypes and misconceptions surrounding mental illness. Most mentally ill people do not commit crimes and should not be feared. Furthermore, mental illness affects people of all ages, races, genders, social classes, professions, etc. In fact, the National Institute of Health indicates that mental illness afflicts one in five American adults in any given year, and yet it remains a taboo and often misunderstood subject (2018).

Even though mental illness can be caused by environmental stresses, genetic factors, biochemical imbalances, or a combination, many view those with mental health conditions as “weak” or “lazy” or somehow at fault. Some of my own family members and friends have simply rolled their eyes at my pain and chalked it up to my being “dramatic” or “attention-seeking.” So, not only is someone with mental illness feared, he or she is further burdened with additional labels and made to feel “guilty,” “lazy,” or “ridiculous.” It is no surprise that so many people with mental illness feel rejected or ostracized, which only enhances isolation and feelings of worthlessness. When someone is seriously ill, people often rush to his or her aid delivering meals, sending flowers and cards, visiting them, and/or helping with household tasks or children. Cancer survivors are rightfully referred to as “warriors,” “survivors,” and “heroes.” But even though those with mental illness suffer, fight, and overcome tremendous battles as well, they are seldom honored and celebrated. Many survivors of serious health conditions say they could not have done it without the support of family, friends, colleagues, neighbors, yet many with mental illness find themselves with little support and few allies.

The shame and stigma with mental illness is so prevalent that some would rather suffer in silence (or even end their lives) than admit they have a mental disorder and seek help. Suicide is the 3rd leading cause of death in youths 10-24 and these rates are only rising (NAMI, 2018). Adolescents suffering from clinical depression increased by 37 percent between 2005 and 2014 (John Hopkins Health Review, 2017). Approximately 11 million U.S. adults aged 18 or older had at least one major depressive episode with severe impairment. (NIH, 2017). Clearly these statistics indicate a dire need for mental health intervention, yet there remains a significant deficit in providers and insurance coverage. Mental health programs continue to be cut or insufficiently funded. Research shows that nearly 60% of adults with a mental illness did not receive treatment (NAMI, 2018). With the lack of accessible treatment and the cost of comprehensive mental health care, on top of the stigma, it is not surprising that depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide (World Health Organization, 2017).

With limited access to care, those with mental illness often self-medicate with drugs and alcohol. In fact, 10.2 million adults have co-occuring mental health and addiction disorders (NAMI, 2018). Sadly, drugs and alcohol can be quicker and easier to obtain than an appointment with a therapist or psychiatrist. Furthermore, adding drugs and alcohol to mental illness compounds an already precarious situation. Mental illness can even be triggered by the use of drugs and alcohol. Like most illnesses, early intervention is key and yet little is being done with regards to mental illness other than sensational news coverage and punitive measures. There are valiant community efforts, support groups, dedicated volunteers, and a variety of helpful services and programs, but they are often limited in size and finances.

When will those with mental illness be treated with the dignity they deserve and not forced into silence and shame? When will mental health coverage and the number of providers and services meet the need? There is no simple solution, but each step, no matter how small, makes a difference. Each donation to mental health organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness or the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), each time we speak out for those who cannot or lend a hand or call a friend, we are one step closer to change.

We never know who might be affected. It could be a family member you haven’t heard from in awhile, or a friend who suddenly stops coming to social events or a colleague who is out on a “medical leave.” It might be a child who smiles and seems to have it all, but self-harms behind closed doors. Now is the time to speak out, to share stories, to withhold judgment, to offer support, to seek treatment, to break down the wall of stigma before it takes the life of someone you know and love.